Men and Machines

Imagination will often carry us to worlds that never were. But without it we go nowhere. – Carl Sagan (Cosmos, 1980)

Since the dawn of civilisation, humans have gazed up at the stars and planets overhead. Even now, separated from our forebears by an expansive gulf of time, technology and knowledge, the stars remain distant, esoteric but evocative targets. Our curiosity and thirst for understanding drives us on, pushing the limits of human endurance, engineering and science to the point where 528 humans from 38 nations have flown beyond the tenuous envelope of gases clinging to the surface of the Earth into wilderness of space. A first, unsteady and cautious step into the vast unknown that surrounds our tiny globe. Of these, only 12 have stepped foot on the surface of the Moon. At over 385,000 km away, reaching the desolate face of our lunar companion remains the pinnacle of manned spaceflight capability, yet it is a mere stone’s throw from Earth in astronomical terms. We peer out from the relative safety of our home, edge into the abyss that surrounds us and tentatively contemplate its content.

The delicate squishiness of the human form is not conducive to the hostile environment of space. Fleshy bags of meat and fluids don’t travel well in a vacuum, the near absolute-zero temperatures dessicate skin and lung and our fragile bones snap and break easily under undue strain. Bombarded by radiation, and far from the protective effect of the ozone layer, our cells mutate and die. Ingenuity and engineering have surmounted these problems in the short term by wrapping our bodies in spacecraft and suits, but the frailties of our terrestrial form remain.

As with many aspects of our lives, we have increasingly outsourced the monumental task of space exploration to robotic envoys. Obedient, unfaltering and better able to withstand the hardships of space travel, these metallic pioneers are our eyes and ears in the depths of space, straddling the boundary of the known and unknown to help us elucidate the mysteries of our near and distant planetary neighbours. Beacons in the fog, they light the way out into space.

Moreover, these scientific emissaries are more than merely (very expensive) collections of navigational equipment, cameras, sensors and propulsion. They are more than laboratories, more than the experiments they conduct, or the raw data they return. More too than the images they record, most never seen by the eyes of a human. These magnificent machines, representative of the peak of human exploratory technology are much greater than the sum of their parts. Often the result of years of international collaboration, teamwork, anguish and joy, these are the ambassadors of our knowledge, the manifestations of the spirit of human curiosity and the first steps of a lonely species wandering out into the darkness. Whilst they wander space in isolation, they have the dreams and imagination of many people behind them.

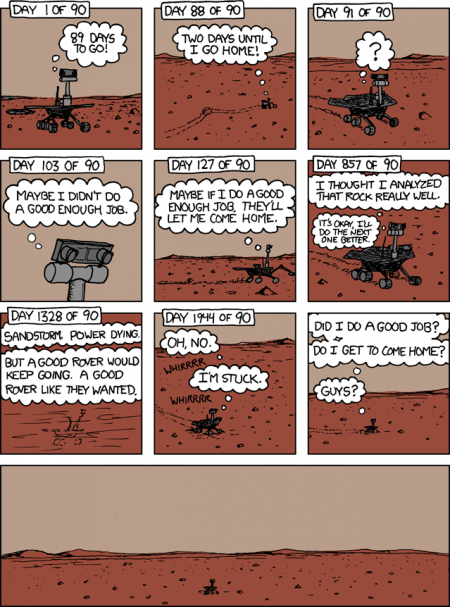

This is why, when a launch fails or an unmanned probe goes missing, the loss is felt by us all. The cost can be counted in dollars or euros, but the real price is the setback to the campaign for understanding that our failed or lost probe was spearheading. A scout lost to the enemy. I’ve heard stories of folks who cried at the loss of Beagle II (the British-built Mars lander lost to the Martian atmosphere in 2003/4), and who amongst us are not moved by xkcd‘s wonderful homage to the late (but very successful) MER Spirit rover?

On the eve of the landing of MSL Curiosity, the most complex rover ever designed, it is worth bearing in mind the hard work and dedication that it took for the latest generation of scientists and engineers to push the limits of our understanding and put a car-sized robot on Mars. I wish all those involved in the construction and operation of this wonderful machine the best of luck. Earth is rooting for you!

Follow the landing live at JPL’s site here