Bonfire Night: When everyone appreciates chemistry

Remember remember the fifth of November; gunpowder, treason and plot… At this time of year children and adults throughout the UK dress up warm and brave the winds and rain in order to watch a human effigy burn on the bonfire while thousands of pounds of fireworks explode in the sky above. For those who are unfamiliar with this seemingly bizarre tradition, it stems back to 1605 when Guy Fawkes tried to blow up the Houses of Parliament using several barrels of gunpowder. While and his fellow conspirators were caught, tried, and executed, several bonfires were lit around London to celebrate the fact that King James I had survived the assassination attempt. During the ensuing years, the annual burning of the ‘guy’ on the bonfire served as a reminder to each generation that treason would not be forgiven or forgotten. Nowadays, however, it is really just a chance to be treated to a spectacular night-time display.

Traditionally fireworks used the same explosive mix of potassium nitrate, charcoal and sulphur as Guy Fawkes had in his gunpowder. The discovery of this ‘black powder’ dates back as far as the 9th Century, when it was first used in China. Unsurprisingly, therefore, China is also attributed with the invention of fireworks, and remains the largest manufacturer and exporter of fireworks in the world.

It is easy to appreciate the skill that goes into producing massive firework spectacles, particularly when they are set to music and combine both aerial and ground-based displays. However our real fascination with fireworks comes in the size, sound and colour of the explosions themselves, all of which are controlled by the chemical composition of the rocket…

The size of the firework essentially depends on the amount of explosive material packed within; the more gunpowder (or equivalent substitute such as Pyrodex) that is used, the greater the force that will explode the rocket and the larger it will appear. Apparently the largest rocket ever produced weighted 13.4 kg and was launched at a Firework Symposium in Portugal in 2010.

The characteristic whistling noise of fireworks is created by resonating gases emitted as the rockets shoot up into the night sky. Salts such as sodium salicylate are added to an oxidising compound (typically potassium perchlorate) to form a propellant fuel that emits gas as intermittent rapid bursts and creates the distinctive screeching noise.

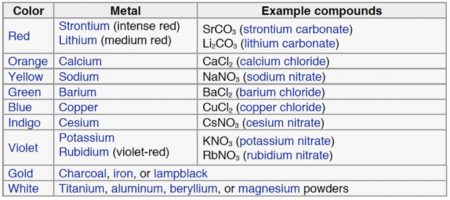

The colour of a firework is the aspect most dependent on chemistry. Stars containing chemical compounds of the desired colour are packed into the rocket and are emitted when the firework bursts. As the stars burn the constituent metal atoms absorb energy, become exited, and emit coloured light as they return to their ground state. Different elements emit light at specific wavelengths thereby generating the different colours. This is exactly the same principle used in Atomic Emission Spectroscopy, albeit on a slightly more dramatic scale.

Of course I’m no expert on the chemical components of fireworks; most of this information has come from the fantastic sources below that are well worth a read. Nonetheless, it’s refreshing to know that many of the elements that I am so familiar with have an aesthetic appeal that brings joy to so many people. If only I could say the same about my strontium isotope data…

http://geology.com/articles/fireworks/

http://www.chm.bris.ac.uk/webprojects1997/RebeccaH/

http://highmaintenancemom.com/drupal/node/151

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fireworks