Professional Culture: Let’s Talk Tackling of Inequity, Injustice, and Absent Talent

As detailed among both previous contributions to this blog and community discussions (Berhe et al., 2020; Cooperdock et al., 2020; Hori, 2020; Marin-Spiotta et al., 2020; Riches, 2020; Riches et al. 2021 and references therein) much evidence demonstrates that scientific excellence suffers from our failings to attract and retain the full array of talent and ways of thinking represented across the globe. In these earlier works, we (the European Association of Geochemistry Diversity Equity and Inclusion [EAG DEI] Committee) and other geochemists called for deep reflection on the broad sweep of social conditioning, varied lived-experiences, and cognitive biases that we are each – without exception – subject to. Similarly, pause for self-critical contemplation of practices capable of discrimination and exclusion (unintentional or otherwise) is encouraged. Progressive reforms and community kindness are advocated for by our professional bodies, highlighting that opportunities to attract and promote all kinds of talent in geochemistry at every stage of a career path should not missed. Yet, we have both an individual and collective duty to acknowledge and correct with urgency those aspects of our professional cultures and workplace systems that are predicated on injustice and sometimes result from unfair legacies of the past.

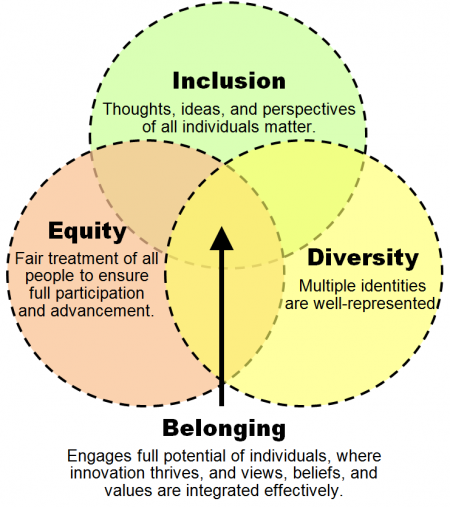

But what are we talking about exactly? In truth an awful lot; much more than we can ever tackle and bring to full reform by ourselves as a committee or as activists in our resident nations. We hope that everyone is or will be involved in driving progress to bring in, retain, and empower all talent. Further, we should reach out and engage with expertise among social scientists and educational / workplace psychologists that, as physical scientists, we recognise a need for and must learn from. The scope of our work can be framed under the working definitions of key terms given below.

The terminology explored here is intended to ease discussions during the forthcoming Goldschmidt Conference. The definitions provided were developed for the EAG’s DEI Strategic Plan that is presently a work in progress, and an activity shared with the Geochemical Society. As with all of our efforts – we hope that community members will be enthused by the ideas for reform that we put out there, all will feel welcome to join discussions, and people will be happy to provide critical feedback to our team or to the EAG Council.

Definitions

Diversity: The EAG adopts the definition of “diversity” as outlined by the American Geophysical Union (AGU) in considering this to be the full spectrum of personal attributes, cultural affiliations, and professional or socioeconomic status that characterise individuals within the society. Collectively, these identities inform and shape one’s scientific ways of thinking. The EAG justly values diversity because it catalyses productivity in the geochemical sciences, fosters the professional success of the EAG’s members, increases the vitality of the EAG organisation, and enhances the societal relevance and impact of EAG science.

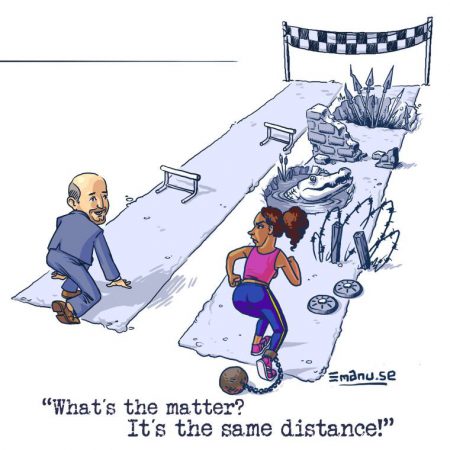

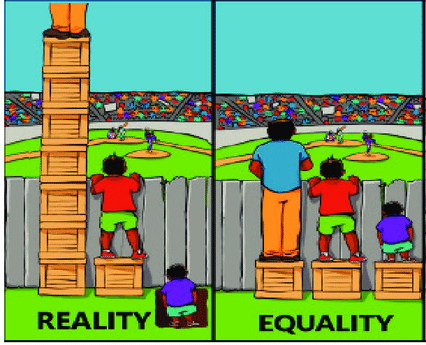

Equity: Whereas workplace and social equality strives to treat each person without difference, equity takes matters a step further in aiming to provide for a range of needs and is at the forefront of the DEI Committee’s efforts. The EAG considers equity to refer to fairness and equality in outcomes, not just in access to support and opportunities.

We believe that equity is an ideal worthy of focused attention, significant resources, collective energies, and continuing dedication. To help achieve that end, EAG’s DEI Committee considers not only that our appreciation of standards should reflect the high intellectual goals of community members, but must also take account of the circumstances under which achievements are realised, the wider contributions that individuals make to improve the profession and its public image, and their accomplishments in building communities while advancing their capabilities. These considerations must run alongside critical treatment of potential bias, discrimination, and stereotyping that have been deeply embedded in STEM up to this point.

To achieve equity the EAG is consciously seeking to remove persisting unjust barriers and to acknowledge and take account of differences among groups and individuals with varying professional privileges, personal identities, and lived experiences. Examples of areas of current focus include providing recommendations to reform our awards and processes of recognition [GCA; link 2a], supporting mentoring schemes and early career programmes [link 2b], spearheading the first ever dedicated studies of our community, platforming personal stories via the EAG blog, and appraising journal editorial boards while suggesting some constructive new practices [Elements, in review]. We intend for equity to be brought about by visionary schemes that purposefully increase opportunities, dismantle problematic procedures, and identify and shatter detrimental systemic and cultural problems. Hence, hitherto marginalised and / or disenfranchised groups of people will no longer be undermined, underestimated, overloaded, or held back. These activities liberate the full community to realise its true potential by creating more vibrant and dynamic cultures that boost innovation and scientific excellence.

Inclusion: The EAG also adopts the AGU definition of inclusion as valuing the contributions of diversity to the broad-based geochemical sciences and respecting the individual identities of participants engaged in executing EAG’s vision, mission, and strategic priorities.

Inclusion encompasses proactive and authentic undertakings (including positive or affirmative actions) that mandate fair and equitable access to EAG membership and to all EAG programs, resources, all forms of honours and awards, leadership positions, editorial board appointments, and other roles of prominence regardless of personal identity and background. Our approaches will ensure that EAG is a safe, welcoming, and supportive environment for all geochemical scientists.

Targeted efforts to eliminate barriers and to bring about equity and advance inclusion in geochemistry include our commitment to the driving of policies, practices, informative educational programs, and further specialist initiatives that actively invest in and inspire previously excluded, underrepresented, and underserved groups. We strive for inclusivity because it augments the quality and impact of the geochemical enterprise and its workforce; it directly supports the personal fulfilment, career success, sense of belonging, and the impact of EAG members by facilitating their contributions. Holding such values and taking action are, quite simply, morally and ethically the right thing to do.

What is marginalisation?

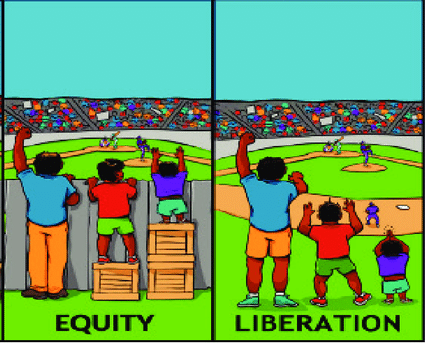

We often talk about people of certain identities or intersections thereof being underrepresented among us, in senior roles, and / or through professional recognition relative to their proportions in the scientific community or society at large. Does underrepresentation result from experiences or processes that deter and / or marginalise such people? Could real and / or perceived marginalisation be responsible for recruitment failures and subsequent losses of bright minds to other sectors?

Marginalisation arises from bias or bigotry and is a form of oppression involving acts and behaviours that disadvantage and relegate affected people and groups to the fringes. Marginalising attitudes, cultures, and / or inequitable practices can be unconscious or intentional, and can be linked to harassment, bullying, and victimisation; it undermines trust, permanently so in some cases. Though marginalisation is generally rooted in bias held by individuals, it can also be thought of as a problematic systemic and structural force where intent or lack thereof makes no difference in it being discriminatory. Any form of marginalisation can devastate higher education or workplaces and is directly opposed to the DEI agenda and the fostering of belonging for all. As such marginalisation raises the utmost concern. To help the community recognise and tackle such problems we have developed a definition that is quoted below.

Marginalisation = To relegate to an unimportant or powerless position within a society or group.

In educational settings or workplaces, marginalisation happens because a person or group, usually but not always one that is in power or possibly tempted by personal gain, such as a manager or dominant social group, has negative preconceived notions (conscious or unconscious) about a colleague, set of people, or direct report. This is a form of prejudice and will result in the subject of marginalisation being treated detrimentally and undervalued. Consequently, this marginalisation leads to a toxic and / or unsafe learning and working environment for the affected person. Marginalising acts can include:

- unequitable curricula or provision to support the needs for a person(s) career and / or reduction of access to equipment and other resources for affected people;

- obstructing / excluding, diverting, deterring, or otherwise impeding a person or persons from formal and informal professional interactions, beneficial opportunities, roles of responsibility or strategic influence and prominence, outreach activities, outputs (e.g., publications), meetings or other events;

- dominant or privileged others, with or without a power imbalance, raising unreasonable workloads / deadlines, sabotaging, misdirecting, stalling, or taking credit for the ideas and work of the person or people being marginalised;

- dominant groups or individuals of that group failing to recognise or acknowledge a person’s or group’s achievements in the workplace and during all forms of professional assessment;

- assigning demeaning tasks and / or disproportionality overloading people with work that is not valued by an employer, recruiter, community recognition schemes, and / or funding body;

- conscious or unconscious affinities and perceptions among committees of a person’s or group’s brilliance or competence based on (traditional, extroverted, or “alpha”) behavioural traits, elitism, first language, accent, self-expression, and other professional qualities – such as decisiveness and assertive competitiveness – associated with leadership styles that may be more prevalent among majority groups (Eagly and Karau, 2002; cf. vitae for depictions of attributes among a wide range of leadership types);

- more generally, professional societies, employers, funders, and other bodies being too rigid or restricted in the contributions and the criteria that they consider and reward;

- the use of derogatory, impolite, objectifying, hostile, passive-aggressive, or threatening language and / or non-verbal expressions, physical or other aggression, and / or bullying / victimising people;

- spreading malicious gossip / innuendo or singling someone out in other ways that denigrate, discredit, and / or relate to a personal characteristic or the symptoms of illness, disability, or neurodiversity, and;

- gaslighting (cf. Ni, 2020), coercive control, or being disrespectful in other ways in order to malign, undermine dignity, or make a person or set of people feel less valuable;

- failure to listen to, respect, and consider the concerns of affected people or groups and / or treating those who raise concerns unfavourably.

Marginalisation most commonly occurs through a series of egregious encounters with limiting attitudes and ostracising acts, or can be experienced as an isolated and potentially grievous incident. Marginalisation can damage the mental, emotional, financial, and physical wellbeing of individuals or groups of affected people, and can be responsible for slowing or blocking their professional progress – all of which are forms of harm.

Faced with systemic, conscious, or unconscious exclusion and consequently having suffered, marginalised people often become disenfranchised with their sector of employment, disengaged with their work and even more isolated. They report feelings of anger, fear, depression, anxiety, sadness, and stress, all centred about something out of their control; the insecurities, blatant bigotry, and prejudice of others. Such unpleasantness is harassment and where properly recorded and / or reported, civil and / or criminal prosecution against the persecutors (individuals, groups, and / or their employing body) can arise with just outcomes in favour of affected people that can lead to media coverage with reputational consequences (e.g., Sharma, 2019; Wadman, 2019; Murugeso, 2020; Yeomans, 2020).

In being both a barrier to the advancement and happiness of talented and deserving people, marginalisation is emblematic of a higher education or work environment and / or community culture that is exclusive and deeply discriminatory. Marginalisation impacts disciplinary reputation and inhibits the attraction and retention of talent thereby stifling our competitiveness as a scientific discipline and as a learning and employment destination on the global stage (e.g., Bhopal et al., 2015; National Academy of Sci., Eng., Med., 2016; Aitsi-Selmi and Simpkin, 2018; Mohamed and Beagan, 2018; Brown and Leigh, 2020; Kwake and Ogunbiyi, 2020; Brown, 2021). Hence, marginalisation must not and shall not be tolerated as it is a cancer to geochemistry, wider STEM, and society at large.

Teamwork

Challenges to the DEI vision and mission transcend disciplinary, employment sector, and geographic boundaries. Some countries may have more socio/cultural, systemic, and legislative barriers than others. Inequalities of various kinds can be enormous and beyond the imaginations of some. Employer leadership is often composed of senior staff selected from among multiple disciplines. As a community we should come together in doing what we can not only to raise awareness as widely as possible, but to go further in actively engaging with large organisations and unions to mandate change that progresses friendly cultures while removing system-wide and multi-sector barriers thereby helping all people everywhere.

Only with the collective support, courage, and energies of all those in our subject area and beyond will the reforms and vibrancy that we dream of be realised.

References

*denotes presenting author at the forthcoming 2021 Goldschmidt Conference

Aitsi-Selmi A. and Simpkin T., 2018. Toxic workplaces are feeding the impostor phenomenon – here’s why. Theconversation.com Link

Berhe A.A., Hastings M., Schneider B. and Marín-Spiotta E., 2020. Changing Academic Cultures to Respond to Hostile Climates. In Addressing Gender Bias in Science & Technology (pp. 109-125). American Chemical Society. Link

Bhopal K., Brown H. and Jackson J., 2016. BME academic flight from UK to overseas higher education: aspects of marginalisation and exclusion. British Educational Research Journal, 42(2), pp.240-257. Preprint Link2

Brown N. and Leigh J., 2020. Ableism in Academic: Theorising experiences of disability and chronic illness in higher education. UCL Press. Link

Brown N., 2021. Lived Experiences of Ableism in Academia: Strategies for Inclusion in Higher Education. Policy Press. Link

Cooperdock E.H., Labidi J., Dottin III J.W. and Keisling B., 2020. Black Lives Matter: Promoting Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Geochemistry. Elements, 16(4), pp.226-227. Link

Eagly A.H. and Karau S.J., 2002. Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109(3), p.573. Link

Hori R.S., 2020. Progress and problems of gender equality in Japanese academics and geosciences. Advances in Geosciences, 53, pp.195-203. Link

Kwake C., and Ogunbiyi O., 2020. Taking Up Space: The Black Girl’s Manifesto For Change. Merky Books. Link

Little S.H., *Labidi J., Riches A.J.V., Bots P., Anand P., Arndt S., Li Z., Maters E., Marin-Cambonne J., Chi Fru, E. and Pourret O., 2021. Constraining Geochemistry’s Community Demographics. Goldschmidt abstract #7356.

Marín-Spiotta, E., Barnes, R.T., Berhe, A.A., Hastings, M.G., Mattheis, A., Schneider, B. and Williams, B.M., 2020. Hostile climates are barriers to diversifying the geosciences. Advances in Geosciences, 53, pp.117-127. Link

Mohamed T. and Beagan B.L., 2019. ‘Strange faces’ in the academy: experiences of racialized and Indigenous faculty in Canadian universities. Race Ethnicity and Education, 22(3), pp.338-354. Open Access Link Link2

Murugesu J., 2020. Universities are failing to address racism on campus. Times Higher Ed. Link

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016. Barriers and opportunities for 2-year and 4-year STEM degrees: Systemic change to support students’ diverse pathways. Link

Ni P., 2020. 7 Signs of Gaslighting at the Workplace. Psychology Today. Link

Pourret O., Anand P., Arndt S., Bots P., Dosseto A., Li Z., Carbonne J.M., Middleton J., Ngwenya B. and Riches A.J.V, 2021. Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion: tackling gross under-representation and recognition among talents in Geochemistry and Cosmochemistry. Invited Review, Geochemica et Cosmochimica Acta. Preprint link

Riches A.J.V., 2020. Writing for Change. Invited Feature, EAG Blog. Link

Riches A.J.V., Pourret O., and Little S.H., 2021. Uniting to Advance Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in a Pandemic and Post-Pandemic World. Feature, EAG Blog. Link

*Riches A.J.V., Pourret O., Ader M., Anand P., Arndt S., Bots P., Dosseto A., Li Z., Marin-Carbonne J., Middleton J. and Ngwenya, B., 2021. Under-representation of Talents among Awards in Geochemistry and Cosmochemistry. Goldschmidt abstract #7155. Link

Sharma R., 2019. ‘We must remove the veil of silence’: Here’s why activists say universities’ use of NDA ‘gagging orders’ shouldn’t be tolerated. iNews. Link

Vitae. Lenses on the Vitae Researcher Development Framework. Link

Wadman M., 2019. Boston University fires geologist found to have harassed women in Antarctica. Science. Link

Yeomans E., 2020. Institutional racism ‘rife at universities’. The Times. Link